When President Obama called for raising the federal minimum wage in his 2013 State of the Union address , he struck a nerve. Some feel it’s about time, while others think the $9.00 per hour he wants isn’t nearly enough. And, of course some would prefer we have no minimum wage at all.

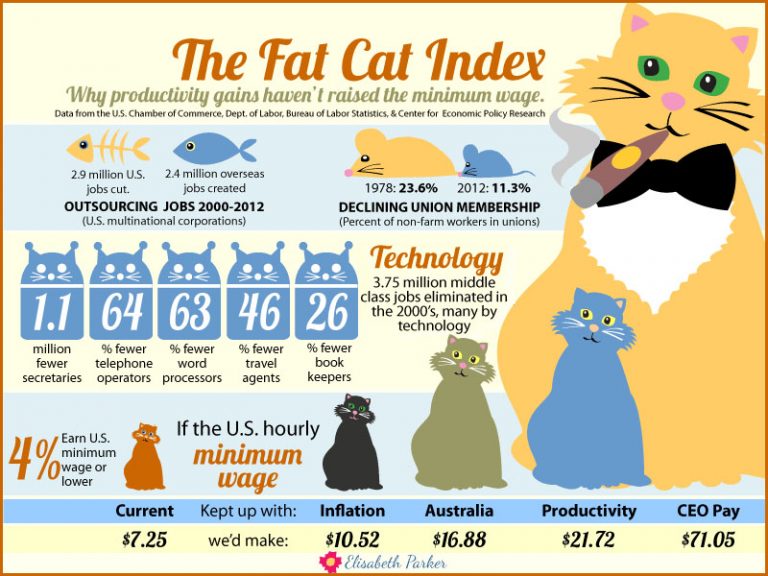

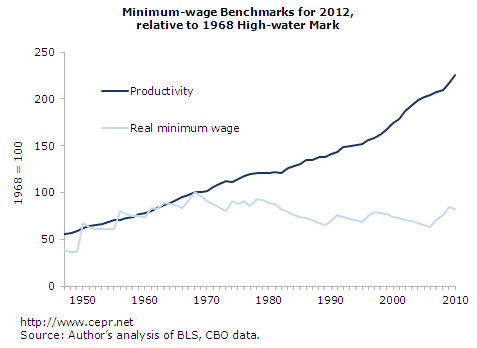

Yet, the current federal minimum wage is still only $7.25 per hour , or $15,000 per year. That’s not even close to a living wage anywhere in the country. In 2012, the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) revealed that if the minimum wage jobs kept up with inflation, we’d make $10.52 per hour . If the federal minimum wage kept up with workers’ increasing productivity — as in the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s — our jobs would all be paying at least $21.72 per hour.

Instead, the average hourly earnings of all U.S. employees is $24.05, according to an August 2013 Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) report. Many of us would love having a job that pays $24.05 per hour. But remember, that’s just the average. The few, but weighty, top-earners bring that number way up. A more telling number is the $16.71 per hour median wage for American workers ( BLS , May, 2012). The median hourly wage means that half of us earn more, but half of us earn less. Often a lot less.

The federal minimum wage is even lower than we think.

Although only 1.5 million workers actually make minimum wage, the federal minimum wage sets a base-level standard. When minimum wages stay flat or go down (by not keeping up with inflation), wages for other workers stay flat or go down as well. Non-wage compensation for American workers — like paid time off, health insurance, pensions, and 401K-matching — have declined as well. But here’s the kicker: (Bill) Moyers & Company reports that two million workers make even less than minimum wage on the job. The Fair Labor and Standards Act (FLSA) doesn’t cover farm workers, Good Will’s employees , interns, or tipped employees like restaurant workers.

Does a $21.72 per hour federal minimum wage sound insane because the amount’s so ridiculously high? Or because American workers are so badly underpaid?

The Nobel Prize winning economist Paul Krugman wrote that in 1973-2007, productivity increased by 46%. Meanwhile, our median wages only inched up 15% in the same time period. As personal computing took hold in the 1980’s, and workers adopted new technologies, productivity climbed even more sharply. The AFL-CIO reports productivity increased 88% from 1982-2011. So why’s our federal minimum wage so danged low? The New York Times ‘ Steve Greenhouse writes that stagnant wages are “a major factor contributing to increasing income inequality.” In 1979, the top one percent of earners — CEOs, pop stars, sports heroes, and the like — claimed 7.3 percent of wages. In 2010, they gobbled up 12.9 percent of wages. And that doesn’t even include non-wage compensation, like royalties and investments. Meanwhile, CEO pay went up by a whopping 725% since 1978. Yes, you read that right: 725%. Nice job, if you can get it.

Erik Brynjolfsson, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology economics professor, explains in the Atlantic Monthly:

“Some people think it’s a law that when productivity goes up, everybody benefits. There is no economic law that says technological progress has to benefit everybody or even most people. It’s possible that productivity can go up and the economic pie gets bigger, but the majority of people don’t share in that gain.”

This reflects an ongoing trend with Wall Street and others aggressively claiming more for themselves. But five other factors contribute to the increasingly severed relationship between productivity, the federal minimum wage, and American workers’ pay in general.

Five trends that increased our productivity but lowered the federal minimum wage.

The following five trends contributing to our stagnant — or declining — federal minimum wage were planted in the 1960’s, took root in the 1970’s, and bore fruit in the 1980’s.

- “Greed is good” mentality: Human societies through the ages frowned on greed. We expected the mighty to at least pay lip service to charity, honor, and humility … or come to a bad end. Alas, modern-day Balshazzars , Midases , and Scrooges get lots of validation from the likes of Ayn Rand , and Milton Friedman . Many Americans embraced the fictitious stockbroker Gordon Gekko , who famously said “greed is good,” in the 1987 film “ Wall Street .” We wanted to be like him.

- Free agency: In 1966, a hard-hitting union man started negotiating better deals for his underpaid baseball talent. Soon, they became “free agents,” and all sorts of talented people (and people perceived as talented) started demanding — and getting — more … and more … and more. We need someone like the late Marvin Miller to negotiate for all workers. Maybe then, we’d have a higher federal minimum wage

- Declining union participation: American labor unions fought long and hard for over a century to win rights, standards, and benefits for workers. Their battles lifted Americans out of poverty and into the middle class. But as unions’ influence in American politics increased while jobs and wages began slipping (thanks in great part to conservative policies), their popularity decreased … and then their influence decreased.

- Technology: Workers increased their productivity by embracing computers and technology. But technology also radically changed how people work and how they think about work. Unions failed to keep up with these trends, and lost the next generation of workers. Meanwhile, these newly-minted “ knowledge workers ” struck off on their own, and forgot there’s strength in numbers.

- Outsourcing: As workers gained technical knowledge in the 1980’s and 1990’s, they saw themselves as information technology mavens learning on the job, and moving up in the world. Unions and the federal minimum wage no longer seemed relevant to their brave new world. Then, over the following decades, they slowly learned the bitter truth. When employers began moving our jobs to cheaper locales across the world, we couldn’t do anything to stop them.

NEXT: “Greed is good” mentality.